This article originally appeared in the Fall 2020 edition of The Missouri Times Magazine.

In August, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new saliva-based COVID-19 test developed by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis.

The test, made in collaboration with biotech company Fluidigm, was dubbed a “game-changer” that put Missouri at the forefront of testing innovation by Gov. Mike Parson. The pandemic has wreaked havoc across the world, including in Missouri.

Below is a conversation between The Missouri Times (TMT) and Dr. Jeffrey Milbrandt (JM), head of the Department of Genetics and the McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University about the new test and how it all came together. Milbrandt’s department took the lead in developing the new test.

Responses have been edited for clarity only.

TMT: How does this new test work?

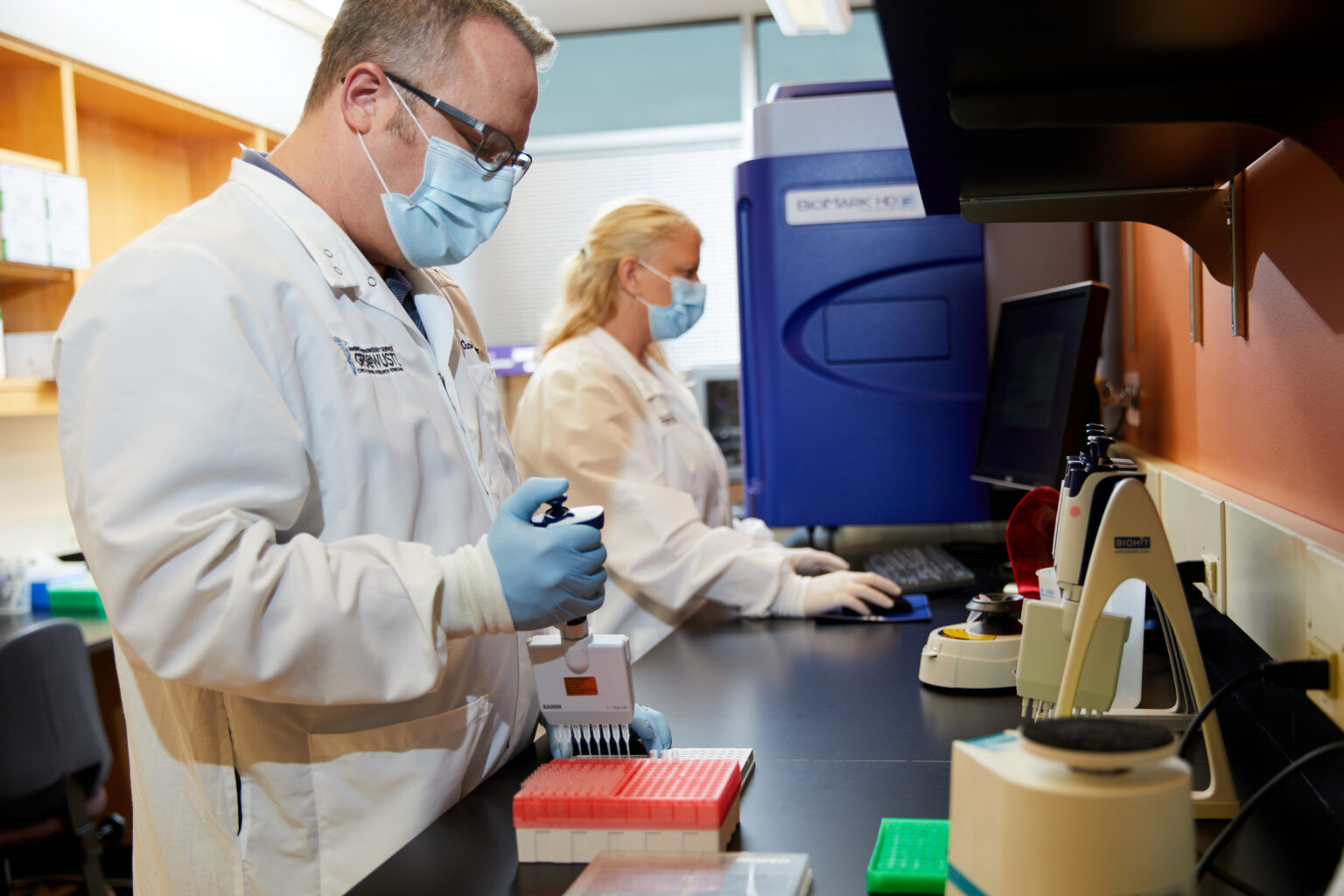

JM: You have a little tube which has a little plastic funnel on it, and then you literally spit in that tube, which has a reagent in it. The tube has a barcode at the bottom that’s read by the robots; so basically we have software that links the data collected to you, and when it’s collected, it’s sent to the laboratory and examined by robots.

In a matter of hours, we read the results via a chain reaction we use to read most genetic tests. It’s a similar type of reaction to what’s been done for around 25 years in genetics biology testing. It’s not so much that we invented anything new — it’s just a different way to collect specimens that’s simpler than the nasal test.

TMT: How long had this been in development? What was that process like?

JM: It really started in mid-March when we realized our lab work would have to be shut down except for pandemic-related research so we set our sights on developing another type of test, and we had this idea that saliva may be a good testing source. The team gradually grew, and we ended up with a large group of people working on it, including informatics teams helping with the sorting and communication of data.

There were many iterations, but one magically worked. It took a huge team of people and departments to get this to work from all aspects.

TMT: How did the relationship between Wash U and Fluidigm come about?

JM: We had experience with an instrument from Fluidigm — which uses microfluidics, very small volumes of reagents — to perform the same test we’ve been performing but on a miniaturized scale and made it automated. So we wondered if we could adapt that saliva idea to Fluidigm’s instrument. We started working with them directly which is why it was a joint announcement. We worked very closely with them on the project.

TMT: What will the cost of the test be — both to produce and take?

JM: The cost should be significantly less [than the nasal test] mainly because you don’t need experienced personnel to collect the specimen and you don’t need to purify the RNA (ribonucleic acid) which takes a whole other set of instruments and kits and more personnel.

Using this microfluidic approach and a largely automated pipeline will cut down on costs as we gear up for thousands of tests.

TMT: When do you expect the test to be available?

JM: The FDA order allows us to use the test now. We’re testing a lot of the Wash U students as they come back to campus and will work with state, county, and city governments to handle their screening processes, and those specimens will be run in batches. It will largely be used as a screening tool for governments, businesses, and universities.

TMT: Gov. Mike Parson has said the test will increase testing volumes. How?

JM: The key point about our test is you can add the saliva directly to the reaction without having to purify the virus or the RNA before you start the actual test process — which eliminates a lot of supply chain issues, cost, and time. We needed to find a way to neutralize the inhibitors in everybody’s saliva. Otherwise, we would have had to go through the whole purification process. That was one of the big obstacles, but it makes the process much faster.

TMT: How long did it take for the FDA to approve the test?

JM: It was an arduous journey. Fluidigm put in an emergency use authorization (EUA) request for the instrument, and we put one in for the test itself. Theirs was approved, and since we developed the test that it was submitted for, we are allowed to use it with their instrument even though our specific request hasn’t yet been granted.

TMT: What does being at the forefront of this innovation mean for Missouri?

JM: When we took this on in March, we had one goal in mind and that was doing something that could impact our community, our local population. We really set out to do it for St. Louis and Missouri, and I think we’ve done that.

TMT: What does it mean to you to be able to develop this?

JM: As head of the Genome Institute, I have a responsibility to bring genomics to the community, and the COVID testing seemed to fit into that. It’s incredibly fulfilling to come up with this test — almost as a side project — and to work with this huge team to develop this for our community.

Cameron Gerber studied journalism at Lincoln University. Prior to Lincoln, he earned an associate’s degree from State Fair Community College. Cameron is a native of Eldon, Missouri.

Contact Cameron at cameron@themissouritimes.com.