JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — Flanked by industry representatives, Sen. David Sater touted legislation aimed at providing greater transparency between the pharmaceutical industry and customers.

SB 971, introduced by the Republican senator earlier this month, would rein in the role of what is known as pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). PBMs operate as a “middleman” between manufacturers, pharmacies, and insurance companies and have been known to engage in spread pricing — the practice of charging insurance holders a higher amount than a pharmacy to make a profit.

This practice has led to increasing drug prices as they hold rebates back from consumers as well, opponents say.

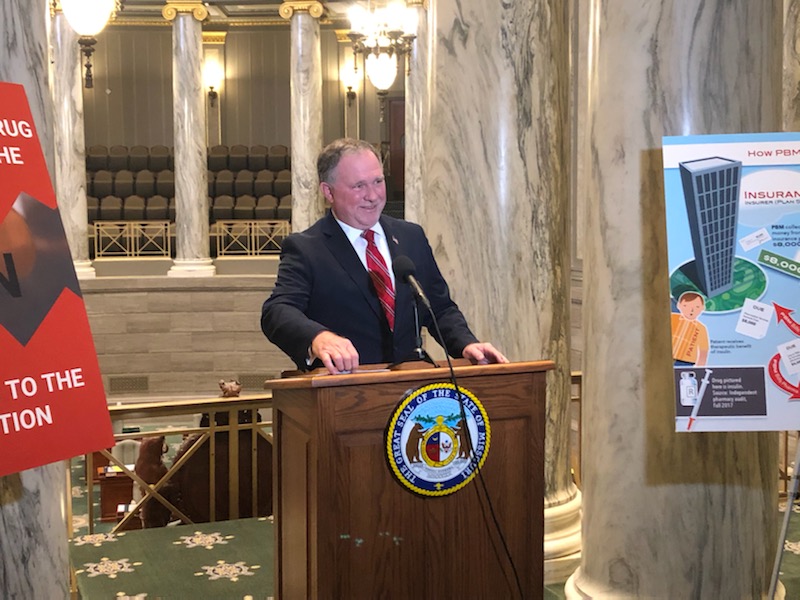

“PBM profit-driving practices block pharmacists across the state from delivering certain medications and result in exorbitant prices for others,” Ron Fitzwater, the CEO of the Missouri Pharmacy Association who led Tuesday’s press conference, said.

Fitzwater continued to explain: “PBMs are not licensed in the state of Missouri. They are the only piece of the drug supply chain that is not meticulously licensed and watched by the state of Missouri, so there’s language in the bill that would require that they become licensed by the state.”

Sater, a pharmacist by trade, further acknowledged the unregulated impact that PBMs have on drug costs in Missouri.

“For far too long PBMs have gone unnoticed and quietly became a contributor to the rising cost of prescription drugs that are burdening patients across Missouri,“ he said. “This bill will balance the scales on behalf of Missouri consumers, resulting in better outcomes and lower costs.”

Sater also contended that PBMs can redirect patients to other pharmacies, limiting choice and hurting independent pharmacies.

“In my district we had one pharmacy that was reliant on a particular poultry industry for most of its business,” he said. “It’s not there anymore because the PBM directed the employees to have to go 20 miles away to get their prescriptions filled.”

Also present at Tuesday’s event was Erica Crane, a pharmacist with MU, who testified about her experiences with these problems from behind the counter.

“It pains me to witness, firsthand, the harmful effects that PBMs have on patients across our state. No one should have to pinch pennies to pay for their prescription drugs,” Crane said.

Loretta Boesing, founder of the pharmaceutical reform group Unite for Safe Medications and a parent who has dealt with the effects of PBMs herself, also participated in the conference. She shared her story of dealing with her son’s health issues while struggling under a PBM’s business practices. She recounted having critical medication mailed to her that was not refrigerated properly by the company, risking her son’s well being.

Similar legislation is being seen in various states across the country. Virginia legislators are debating a similar bill, while Alabama, Arkansas, and several other states have passed new PBM regulations in the last few years.

Cameron Gerber studied journalism at Lincoln University. Prior to Lincoln, he earned an associate’s degree from State Fair Community College. Cameron is a native of Eldon, Missouri.

Contact Cameron at cameron@themissouritimes.com.