JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — After a filibuster that nearly hit the 15-hour mark, the Missouri Senate agreed to a compromise on civil litigation reform, or as it’s more commonly referred to, tort reform, for the first time.

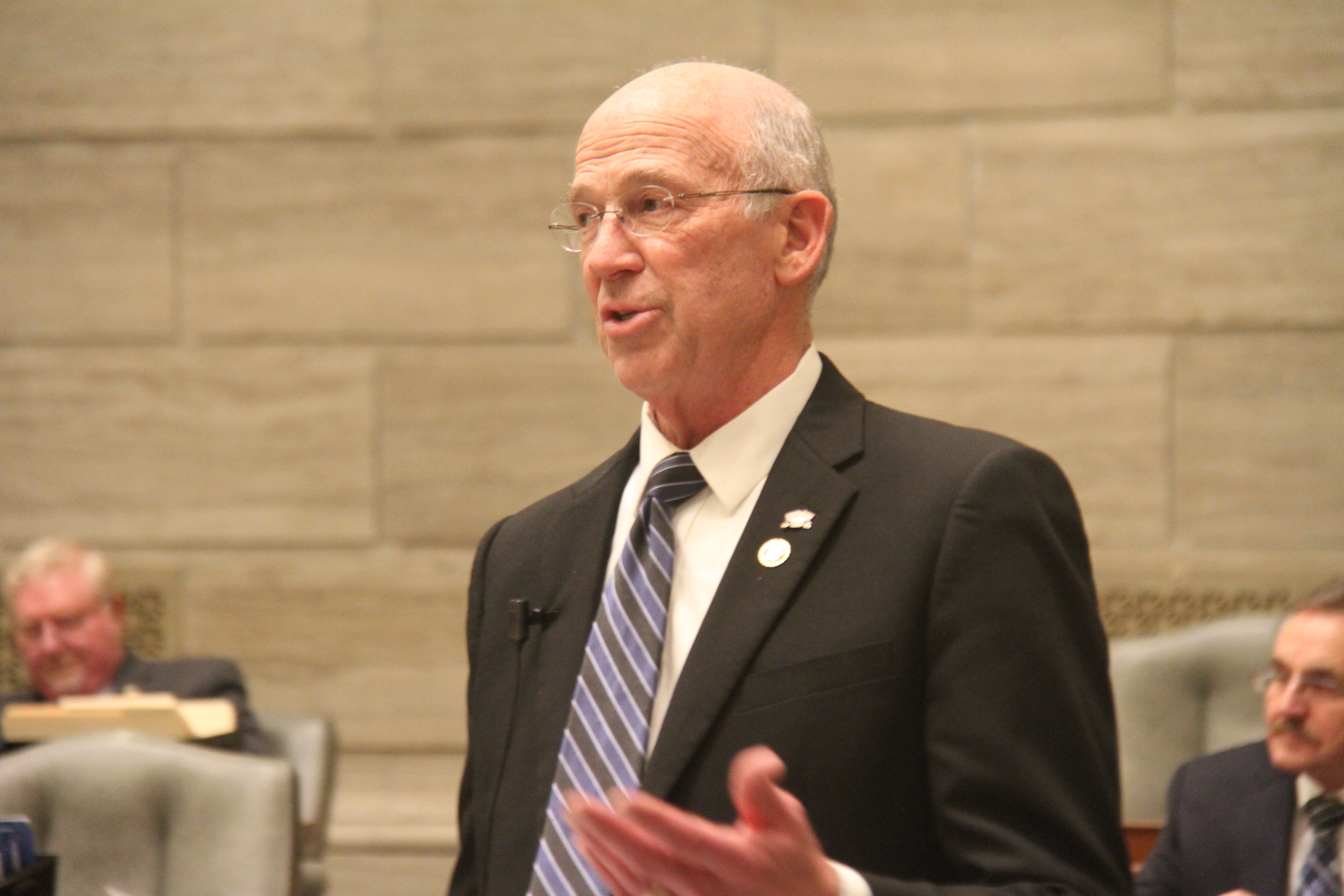

In the early hours of Wednesday — when most people are just waking up — the state Senate perfected SB 7, sponsored by Sen. Ed Emery, which modifies provisions of what and where cases can be joined together.

Tort reform is not a new issue the Missouri General Assembly has attempted to tackle. For the past several years legislation on the topic has been debated, but nothing has crossed the finish line.

During the 2018 legislative session, the House passed a bill that made it to the Senate’s informal calendar. The Senate has their own version, which was brought up for debate on the floor several times but never came to a perfection vote.

“I would very much like to see us get this done this year,” said Sen. Scott Sifton. He had a whole host of reasons for wanting to address the issue this year, including the recent Missouri Supreme Court opinion on joinder and venue.

Currently under Missouri’s statute, tort lawsuits can be joined together if they are based on the same facts, are about the same product or service, and allege the same series of transactions. Any of the state’s courts can handle those lawsuits providing one of the plaintiffs has standing in that court.

Advocates for tort reform attribute those regulations to Missouri courts being clogged. Statistics cited noted that only 1,035 out the 13,252 mass tort plaintiffs with cases in St. Louis City are from Missouri, with only 242 of those are from St. Louis City.

On February 13, 2019, the Missouri high court handed down an opinion in Johnson & Johnson that joinder cannot be used to establish venue. The landmark case helped address some — but not all — of the issues advocates have been hoping to solve for several years relating to tort cases.

“The good news is that a lot of ground has already been covered before we got to the floor this evening. The bad news is that we are not there yet,” said Sifton.

Over the course of more than 15 hours, a compromise was reached that left neither party completely satisfied.

“If both parties are a little bit disappointed, you know you are probably as close as you are going to get to a workable bill,” Emery told the Missouri Times.

The two most significant changes in the compromise proposal was a saving clause referencing the recent court decision instead of defining it in statute.

Based on concerns that language in the bill language went beyond the scope of the Missouri Supreme Court’s ruling, that language was struck and they directly referenced the ruling.

The so-called savings clause allows cases where a trial date was set before February 13, 2019, to continue. The savings clause was the final amendment added to a Senate substitute bill before lawmakers determined the bill perfected.

At the end of the debate, Emery noted that even with the compromises, the bill still works for the issues they set out to address. Sifton called the compromise imperfection, but better than where it started.

Alisha Shurr was a reporter for The Missouri Times and The Missouri Times Magazine. She joined The Missouri Times in January 2018 after working as a copy editor for her hometown newspaper in Southern Oregon. Alisha is a graduate of Kansas State University.