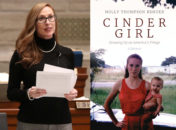

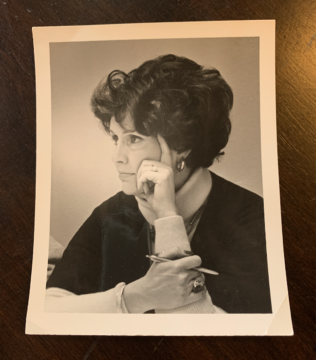

JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — Mary Gant Newquist has always been boldly ambitious, a woman on a quest to learn all she could, to be all she could. And she solidified her spot in the annals of Missouri history 47 years ago when she was elected to the state Senate, the first woman to join the upper chamber.

Newquist had served six years in the House (under the name Gant) representing a blue-collar Kansas City district when the Senate seat opened up. Then, she asked herself one question: “Why can’t I run?”

So she did, becoming Missouri’s first female state senator with her election on Nov. 7, 1972.

Now 83, Newquist said politics was both her “friend and foe.” She is a Democrat but was fiercely independent — backing Republicans when she felt it was right. And she maintains she wasn’t treated differently by her male colleagues in the General Assembly because of her gender.

But nearly half a century later, it’s a “women’s issue” that has gained her some notoriety even to this day: her vote against the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

Media reports at the time — and even now — didn’t paint the full picture of her decision and wrongly put Newquist in the camp of the late Phyllis Schlafly, a staunch conservative from Missouri known for her adamant opposition to ratifying the ERA.

Newquist insists she is a supporter of women’s rights — and her legislative record aside from the ERA vote certainly seems to support that. She championed legislation related to equal pay, spousal abuse, and rape-shield laws. She’s defended Roe v. Wade.

“I am so proud of what women have done and the quality of women in public service has improved dramatically,” Newquist told The Missouri Times over coffee and baklava in downtown Jefferson City. “These women are definitely equal to men, if not superior. And gender really doesn’t have anything to do with it.”

So what was her objection to the ERA? To simplify it, Newquist wasn’t comfortable with the totality of the amendment, the idea of just ratifying it and then letting the courts address it. In a way, Newquist thought the vast changes the ERA presented should “reflect what was going on culturally” and maybe even be tackled piece by piece.

Her objection, too, came down to how a court would interpret what the ERA would mean for conscription, or a military draft, should that arise.

Missouri is one of only a handful of states that have not ratified the proposed constitutional amendment solidifying rights “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on account of sex.” Before the 1977 deadline, only 35 of the needed 38 states voted to ratify the ERA; the fight for it, however, is ongoing.

Now, Newquist said she “vacillates” over whether she’d vote the same way again. There have been many advancements for women — and even other groups — without the ERA, she pointed out. But it’s clear how she was portrayed over her decision still troubles her to this day.

But if Newquist is anything, she’s a sedulous fighter for her principles — and has a sharp sense of humor. In fact, during the ERA fight in the General Assembly, Newquist received a “chastising” letter from a woman who wasn’t her constituent. Instead of taking it to heart, Newquist sent a snarky reply back, along the lines of: “Some idiot sent me this stupid letter with your signature. And I’m returning it to you.”

Newquist’s response ended up in the Kansas City Star, but her colleagues saw the humor in it, she said. In fact, it may have ingratiated herself even more among the male legislators.

“I have had to overcome a lot, and I’m really not that brash, but I will stand up for my principles. I’m a big person who believes in principles, honesty, sincerity — but honesty number one — and don’t fool yourself,” Newquist said. “Look beyond what benefits you and think about what the basic principle is about why you’re doing what you’re doing or believe. Some people would call me simple, but I’m not.”

Newquist was born during the Great Depression and is candid about how her political career impacted her three children as they grew up. Her former husband and father of her children, Ronald Gant, has since died.

While she was running for Senate, Newquist met the man she would become married to for 40 years, the great love of her life: Peter Newquist. He was a banking lobbyist, which caused some controversy at the time as she chaired the Senate Banking Committee. They married in 1979 and remained together until his death earlier this year at the age of 96.

As for the future of politics, Newquist vociferously decries how much influence money has gained over the years.

“When people get the idea that they want to run for office, first of all, you ask why they’re running,” Newquist said. “I wasn’t running to make a career or to make money. I was running to serve because I genuinely loved the people in my district.”

Newquist served in the Senate until 1981, after losing a close primary race to Lee Swinton. After, she was appointed by then-Gov. Kit Bond, a Republican, to chair the State Board of Mediation where she served for more than a dozen years.

“Politics is a business. You have to know how to meet people and sell your platform, sell yourself, and be honest that you’re going to do the right thing. You can disagree and not be totally hateful. You can really calm the waters with humor and a smile.”

“And just a little bit of knowledge can be a dangerous thing,” Newquist chuckled.

Kaitlyn Schallhorn was the editor in chief of The Missouri Times from 2020-2022. She joined the newspaper in early 2019 after working as a reporter for Fox News in New York City.

Throughout her career, Kaitlyn has covered political campaigns across the U.S., including the 2016 presidential election, and humanitarian aid efforts in Africa and the Middle East.

She is a native of Missouri who studied journalism at Winthrop University in South Carolina. She is also an alumna of the National Journalism Center in Washington, D.C.

Contact Kaitlyn at kaitlyn@themissouritimes.com.