JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. – On the first Tuesday of November later this fall, politicos around the country will glue themselves to their television screens, flip the channel to CNN, MSNBC or Fox News and eagerly await the results of the 2016 Presidential Election.

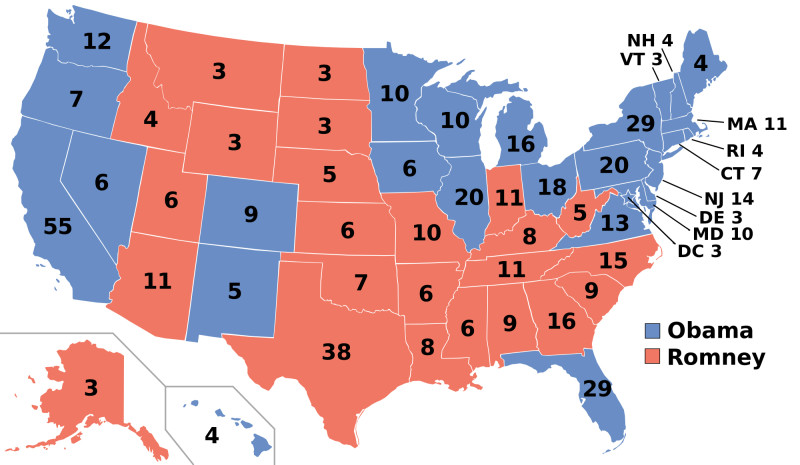

While Wolf Blitzer or Megyn Kelly or Rachel Maddow will dutifully announce the winner of each state, some of them have essentially been decided since the last presidential race. While Democrats and Republicans alike will chew on their fingernails in anticipation and anxiety for results from Florida, Ohio and Virginia, when Texas is colored red and New York is colored blue, not a soul on earth with any knowledge of American politics will bat an eye.

However, a compact of state legislatures around the nation want to change that state by state count and instead institute a national popular vote as the means for electing the next president of the United States. And some Missouri legislators want in on that deal to make the state relevant in presidential elections again.

“Missouri for a long time was a bellwether state that helped predict who the presidential winner was going to be, and over the years, Missouri has kind of lost its prestige and slowly has gone to the Republican side,” Rep. Robert Cornejo, R-St. Peters, says. “Both sides now have just ignored Missouri.”

That ignorance of the Show-Me State is anything but unique. Because of the winner-take-all system instituted by almost all states, states with vast majorities of Democrats or Republicans simply do not receive the same amount of attention from presidential candidates as swing states. Political scientists have known about this phenomenon for a long time, but the actual disparity between swing states and non-swing states is pronounced.

During the 2012 Presidential election, the Associated Press found that nine states received $350 million dollars worth of ads from the campaigns of President Barack Obama, challenger Mitt Romney, and the various PACs supporting each of those candidates. Other states? Virtually none. Fair Vote, a nonprofit that advocates for more representative democracy, found that Obama and Romney, as well as their respective running mates, Joe Biden and Paul Ryan, only made stops in 12 of the 50 states after the Democratic National Convention. Over half of those stops were in just three states – Ohio, Florida and Virginia.

In an effort to mitigate that disparity, multiple states have passed the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which would cleverly use the power of the Electoral College to institute a national popular vote.

The compact works as an agreement through state legislation that designates electors for the Presidential election from a particular state to vote upon the criteria of national popular vote instead of the popular vote of each candidate. For example, if Missouri votes 55 percent for Donald Trump against Bernie Sanders in 2016, then Trump would win Missouri and its 10 electoral votes. However, if this compact were passed in Missouri, then the popular vote of Missouri would not matter. If Trump won Missouri, but Sanders won the national vote, Sanders would get Missouri’s electoral votes.

On the surface, this system seems to misrepresent the voting interests of Missourians, but the compact only goes into effect, somewhat ironically, when it is passed by states who combine for 270 electors – a majority of the Electoral College. Holding that majority changes the metagame of the election from a focus on states with state-majority appointed electors to states appoint electors based on the national vote. In theory, that change means candidates will have to appeal to all parts of the country, not just swing states.

Currently, the proposal has been passed in states that make up 165 electors. Maryland was the first state to adopt the measure in 2007, followed by New Jersey, Illinois, Hawaii, Washington, Massachusetts, the District of Columbia, Vermont, California, Rhode Island, and finally New York. Legislation is pending this year in four other states (Arizona, Michigan, Minnesota and Pennsylvania) and bills filed this year by Rep. Jeremy LaFaver, D-St. Louis, and Rep. Tony Dugger, R-Hartville, would put Missouri on that list.

Yet, the bill runs into some problems here, in terms of partisanship; the 11 states that have signed onto the compact are Democratic strongholds. Cornejo believes the national popular vote has been easier to pitch to solid Democrat states because of the debacle of the 2000 Presidential Election where President George W. Bush won the Electoral College while losing the popular vote. Whether Democrats held a genuine desire to reform the election process in the United States or suffered from a severe case of sour grapes, it became a sticking point with many in the party.

However, that does not mean the idea is unpopular with Republicans. In fact, a 2013 Gallup poll found 61 percent of Republican respondents would vote to do away with the Electoral College. And many that have filed the legislation in the past in Missouri have been Republicans. Still there are concerns on the Right that this compact violates the intent of Constitution and the nation’s founders.

“I did run into some people who said we were trying to change the Constitution and our founding document,” Rep. Lincoln Hough, R-Springfield, says. “That’s not at all the intent, and we’re not doing away with the Electoral College. It’s not a partisan issue. You have supporters on both sides.”

Hough sponsored legislation in 2011 as a first-year freshman that would add Missouri to the compact. LaFaver expanded on Hough’s explanation by arguing the compact is highly constitutional because the constitution grants the right of choosing electors to the individual state legislatures.

“During the Constitutional Conventions there were a number of ways to determine how electors were distributed,” he says. “Should it be based on percentages of population, congressional district… The founders could not come up with a solution, so they left it up to state legislators to decide how that happens.”

In writing, Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution states precisely that, “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress… shall be appointed an Elector.” That language essentially dictates the states can choose how to appoint electors and how those electors represent the state.

LaFaver also contends that the winner-take-all system most states have today did not take hold until around 30 years after the last of the Founding Fathers had passed away. In other words, the current system would be completely foreign to the people who created this country.

Nebraska and Maine are the current exceptions to the winner-take-all system. They use a system called the Congressional District Method which gives each Congressional district in the state one elector who votes as the district goes, then the state’s winner gets the two electoral votes granted by the Senate. That difference proves LaFaver’s point – that states have the ability to assign electors how they see fit.

“It uses the rights granted to the states in Article II, Section 1,” LaFaver reiterates. “So to me, passing national popular vote is a states rights issue.”

Hough says more conservatives are beginning to see it that way as well.

“I got feedback from some of our conservative friends, and now we have conservative organizations that are at least moving towards support of this legislation just as people learn more about it,” he says.

However, the idea is not still without its opponents. Some believe the compact would shift control of the popular vote to major population centers, leading to an ignorance of rural voters and rural issues. LaFaver says Missouri proves this notion is not true.

“If that was the case, then we would see that play out in state popular vote contests, like governor,” he says. “We all know you can’t win the governorship by hanging out in Columbia, Springfield, St. Louis and Kansas City. You’ve got to get out to Dunklin and Pemmiscot and New Madrid.”

Hough says the compact will not pass this year in time for the election, but that it highlights a way for Missourians to get involved in the political process again after becoming just another state cast aside in favor of visits to Ohio and Iowa.

“I saw this as a very balanced and fair way for Missouri to not only get back on the map, but give our citizens, give our constituents a say,” he says.

LaFaver believes that a national popular vote gets America back to some of its foundational principles that each person should have an equal role in the political process.

“Every vote should be equal to one another,” he says.