Missouri’s foster care agency failed to adequately protect or locate children who went missing from foster care or properly provide medical or mental health treatment when located, federal regulators said in a new report Thursday.

The report, from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General, said in the 59 cases of missing children it reviewed, 49 were identified as being at a higher risk of potentially going missing but only seven of those children received services to reduce that risk.

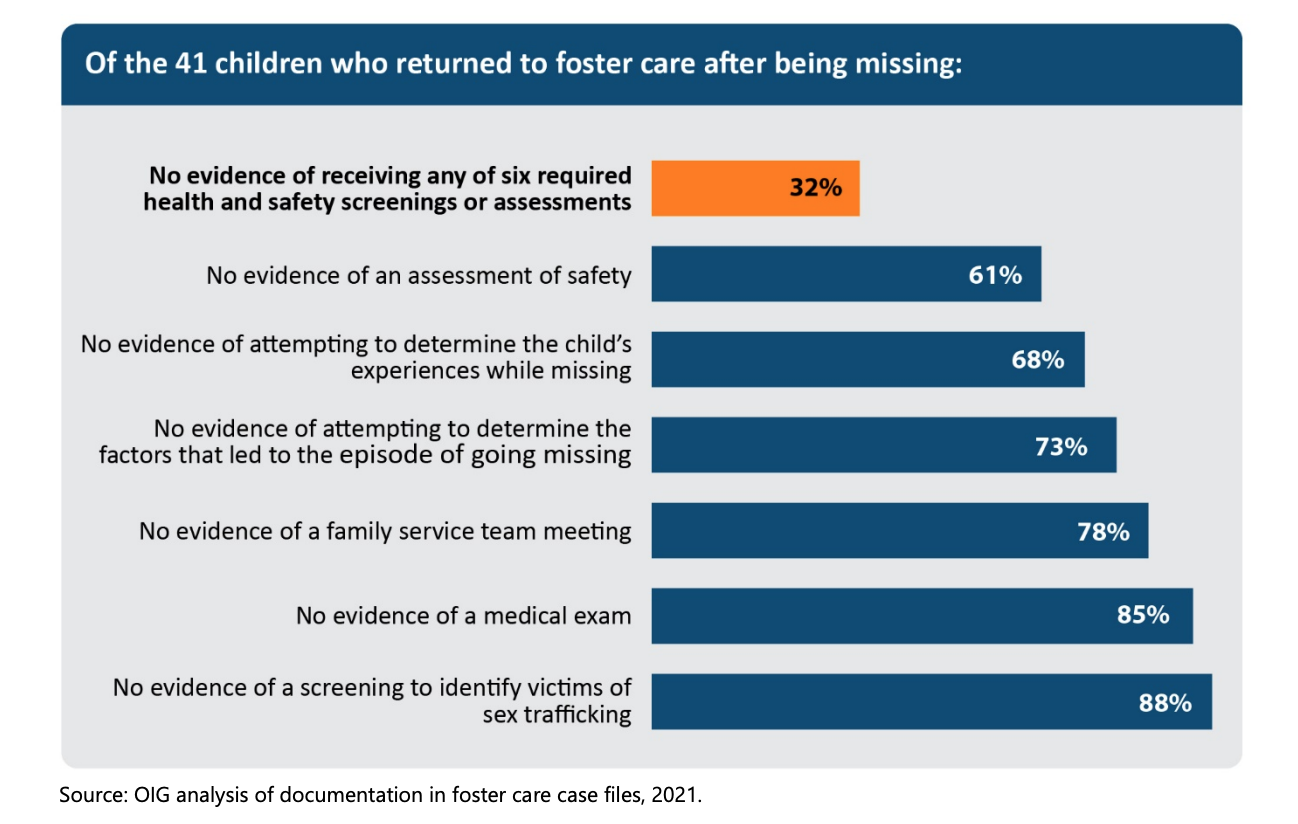

And nearly half of those children weren’t even reported as missing — to local law enforcement officials or the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children — the report found. Additionally, for 1 in 3 children reviewed by federal regulators, required health and safety checks upon their return to foster care were not provided.

One child identified by regulators had been sexually exploited in at least four states while missing, but there was no evidence that the child was reported as missing, the report said.

“The Missouri foster care agency … missed opportunities to identify and mitigate children’s risk for going missing from foster care. Additionally, there is no evidence that once children went missing, Missouri complied with state and federal requirements or effectively used all resources available to assist in locating the children,” the report said. “Further, once the children were located, Missouri appeared to do little to ensure that they would not go missing again, or to ensure that they received supportive services to address trauma they experienced while missing from care.”

‘Small changes will not solve this problem’

Sen. Cindy O’Laughlin, who has dealt with the foster care system firsthand in her family, has spent much time during the interim working on ways to improve the system and the Children’s Division under the Department of Social Services (DSS).

“The entire Children’s Division is in chaos. This stretches from the local [offices] to the top of the department,” O’Laughlin told The Missouri Times. “They are going to have to implement dramatic change to improve, and they need a leader with vision and courage. This is the exact opposite of what government generally chooses, which is why we are at this point.”

“Small changes will not solve this problem,” O’Laughlin added.

Rep. Mary Elizabeth Coleman, chair of the House Children and Families Committee, told The Missouri Times she has reached out to the House speaker for permission to hold hearings on “where and how our system has failed so many of our kids and families.”

In 2019, 978 children in foster care went missing in Missouri, according to the report. Local law enforcement officials, the Office of Inspector General, and the Justice Department banded together in August 2019 to locate children in Missouri’s metropolitan area, finding 23 of those people.

The report said Missouri’s current system cannot distinguish between whether a child is missing or in a known but unapproved location.

Federal regulators recommended Missouri develop policies to help identify children who are at risk of going missing and ways to prevent that from happening. It also recommended the state improve how it identifies those who are missing and implement a system to ensure caregivers comply with procedures and requirements in place for missing and returned children.

In a letter dated Sept. 21, DSS Acting Director Jennifer Tidball said the Children’s Division has developed “human trafficking policy, training, practice alerts, and assessment tools” while the report was still being compiled. It has also expanded its partnership with various organizations to help children who have been trafficked or at a greater risk of human trafficking, Tidball said.

The division has also implemented a checklist of procedures for case managers for when a child is missing and located and is planning to change how children are identified — such as to better designate if a child is missing or in an unapproved placement, Tidball said.

O’Laughlin said any change would not occur without the Children’s Division and local communities working together.

“What is happening is communities want to support and bolster the efforts of the Children’s Division, but at every level, decisions are made which turn people away,” she said in a text message. “This leaves the system unsupported and vulnerable. It is going to require communities AND the Children’s Division working together, and they want to be authoritarian.”

After the initial publication of this report, a DSS spokeswoman emailed: “The safety and well-being of children is a top priority for the Missouri Department of Social Services, and we continue to work on ensuring safety for children in Missouri.”

‘Wake-up call’

Of the missing children found and returned, 32 percent (13 out of 41) did not have evidence in their files that they had received proper health or safety checks when returned — including proper medical exams or services to help if they had been sexually exploited, the report said.

“These health and safety checks are an important first step to understanding the experiences of children who go missing from foster care. Children may encounter dangerous situations, such as sexual exploitation or sex trafficking, and may experience adverse health outcomes,” the report said.

“If these required checks are not performed, children’s trauma may go undetected and children may not receive critical supportive services to help address trauma they experienced while missing from care. A child may benefit from supportive services such as therapy to address the child’s mental health needs, or a change in placement to reduce the child’s risk of going missing in the future.”

Federal regulators found 83 percent of the cases reviewed had at least one factor that would designate them at a higher risk for going missing but only a few had notations in their case files. More than half of those who were missing had previously been missing.

Missouri has policies in place that instruct case managers in how to aid and locate missing children — which is in line with federal law — but regulators found they do not often follow those procedures. Nearly half of the cases reviewed (27 out of 59) had no evidence that case managers reported them as missing.

In her letter to regulators, Tidball said Children Division staff have said law enforcement isn’t always “convinced” that children, particularly those who are older, are actually missing.

“It’s clear from these findings our state’s efforts to prevent this from happening and to respond are insufficient,” Jessica Seitz, Missouri KidsFirst executive director, told The Missouri Times. “I hope this report serves as a wake-up call, and I’m confident we can come together on solutions to keep kids safe.”

This story has been updated to include a statement from a Department of Social Services spokesperson.

Kaitlyn Schallhorn was the editor in chief of The Missouri Times from 2020-2022. She joined the newspaper in early 2019 after working as a reporter for Fox News in New York City.

Throughout her career, Kaitlyn has covered political campaigns across the U.S., including the 2016 presidential election, and humanitarian aid efforts in Africa and the Middle East.

She is a native of Missouri who studied journalism at Winthrop University in South Carolina. She is also an alumna of the National Journalism Center in Washington, D.C.

Contact Kaitlyn at kaitlyn@themissouritimes.com.