Somewhere over Vietnam around Christmastime 1972, a surface air missile locked onto a B-52 soaring 35,000 feet above the ground. Despite the pilot’s best maneuvering efforts, the missile was staunchly locked into its target. The gunner in the back screamed, and the crew of six waited.

And then the missile detonated.

Early.

Wayne Wallingford, Missouri’s Department of Revenue director, can recall with clarity his more than 300 combat missions during the Vietnam War in the 1970s. He can still point out all of the functions of various fighter jets, how they’ve changed and transformed over time, and how they are utilized.

But he has no idea how that missile detonated early — or why the hundreds of pieces of shrapnel that peppered their B-52 missed the controls, fuel tank, and men. (Wallingford said a crew chief stopped counting the holes in their plane at 680.)

Wallingford’s subtle bravery has continued with him throughout his life of service — from his time in the Air Force to his business career to his public works in the legislature and executive branch.

In fact, when Wallingford decided to run for state Senate after serving just one term in the House, the first question a reporter asked him was, “Well, representative, isn’t this a bit risky for you?”

But Wallingford hasn’t been afraid to take risks — in part, because of his deep faith, commitment to his home and family, and unparalleled tenaciousness.

And as Wallingford tells it, “After flying over 300 combat missions in Vietnam, being shot at and hit, you have to redefine the word risk.”

You may know Wallingford,75, from his work as the newest Department of Revenue director or from his time in the Senate and House (twice). But before he represented southeast Missouri in the legislature, Wallingford traveled around the country — and the world — in his 25 years in the Air Force.

Wallingford joined the Air Force in 1968, in the midst of the Vietnam War, after studying business and English at the University of Nebraska.

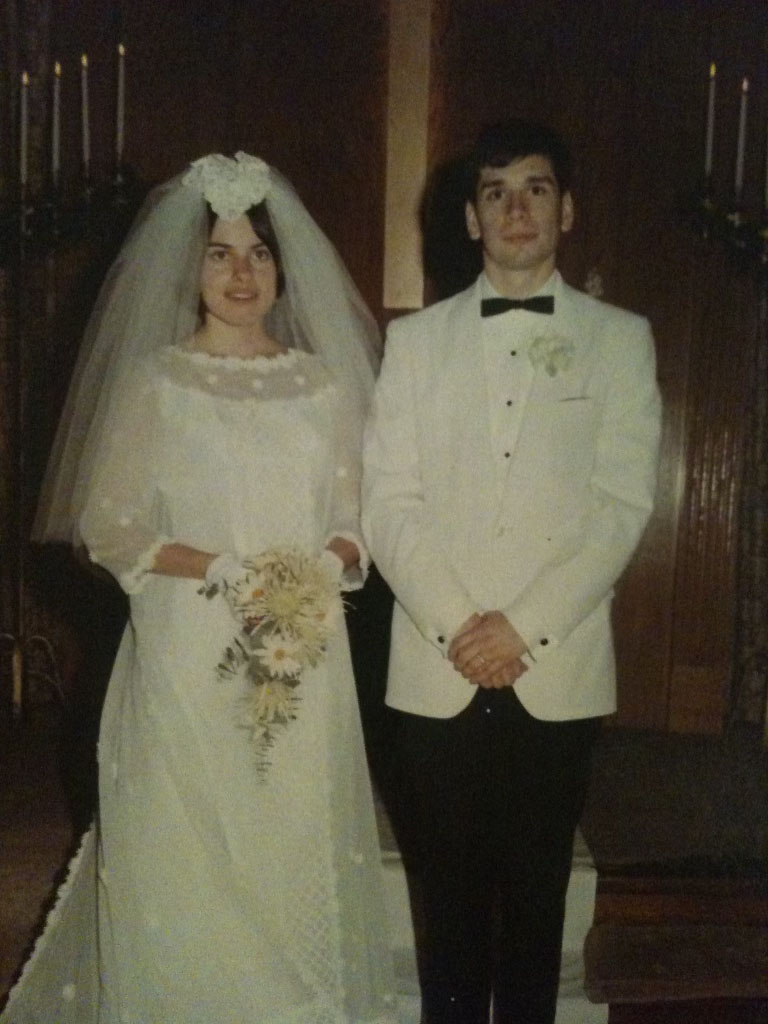

Along with his wife, Suzy, Wallingford moved to California where he underwent trainings in Sacramento and Merced as well as Spokane, Washington. By 1970, Wallingford was transferred to Fort Worth, Texas, where he was stationed when he was deployed to Vietnam for his first tour.

Wallingford was part of the historic Operation Linebacker II aerial bombing mission from Dec. 18-29, 1972 (with a pause for Christmas Day) — a mission credited with ending the war in Vietnam.

Before Linebacker II, no B-52 planes — Wallingford was assigned to a D model— had been lost to combat. But during this mission, 15 were lost. And it was during that mission that Wallinford’s plane was hit with shrapnel from the early detonating surface air missile.

“I’ll never forget to this day when the general came in to brief us for the next mission. He said, ‘Well, we thought we were going to lose a lot more of you than we did,’” Wallingford recalled.

Having always been interested in health care administration and business — he worked for Nebraska Methodist Hospital for a short in between graduation and the Air Force — Wallingford thought he would spend about the mandatory six years in the Air Force after flight training before leaving.

But instead, he continued his service in the military long past Operation Linebacker II, attending Air War College in Montgomery, Alabama, and signing onto a joint tour at Camp. H.M. Smith in Hawaii under the future Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman Admiral William Crowe. Wallingford spent some years in England (a dream for the Austin-Healey aficionado and British Invasion fan who named his firstborn daughter London).

In all, Wallingford served as Chief of the Intelligence Division in England and Chief of the Electronic Intelligence Analysis Division in Hawaii. He was awarded several medals during his service, including the Silver Star.

And it was because of his service in the Air Force that Wallingford would eventually learn of Cape Girardeau, where he’s called home for the past 18 years. In the 1980s, Wallingford was given the opportunity to take a four-year sabbatical to Cape Girardeau where he worked as a professor of aerospace science at Southeast Missouri State University.

Eventually, the Geneva, Illinois-native retired from the Air Force at 47 years old. But he wasn’t done traveling the country and serving.

He joined Taco Bell corporation working as a recruiter in Chicago, overseeing a five-state region. Then he moved to the east coast, settling in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where he was in charge of 16 states and served in various regional management positions.

It was there on the East Coast that Wallingford was forced to slow down — and attempt to retire again. In 2004, he got a call from his doctor that he had prostate cancer. He underwent surgery, thinking he’d be back on the road, visiting stores, that same day. But the medication he was prescribed left him lethargic and unable to move as sprightly as he once could.

His medical leave ended in July, but Taco Bell offered to let him take the rest of the year to rest, maybe work part-time if he felt like it, and keep his full salary and benefits.

Wallingford thought that wouldn’t be fair to the other workers — and he wanted to go out on top. So he retired and moved back to Cape Girardeau in the fall of 2004.

Retirement didn’t last too long. Back in southeast Missouri, Wallingford’s son-in-law had just lost his own father and was left with several McDonald’s franchises to own and operate. He convinced Wallingford to join him, even if it was just to impart his business acumen, and Wallingford eventually became a chief people officer for the employees at nearly 20 restaurants.

Wallingford stressed that he made sure to take care of his employees in that capacity — and his consideration of other people has been greatly evident throughout the years.

“If you ever get the chance to sit down with Wayne Wallingford to talk about his life and the experiences that have made him who he is, carve out a couple of days (yes, that long) and do it,” Senate Majority Floor Leader Caleb Rowden, who served with Wallingford in the General Assembly, said. “Wayne is an incredible man with an incredible story. The legislature is a better place because he was there.”

“I love people. There’s no stranger when I’m around. I love talking to people because I find we have so much in common because I’ve lived all over the world with the Air Force and Taco Bell, and I’ve lived in many states,” Wallingford said. “No matter what they come up with, I’ve got a connection to it. I love talking to people and finding out about them.”

It was one of his connections in Cape Girardeau who convinced him to run for state representative in the first place. And in the legislature, Wallingford made a unique promise that he stuck with (despite the constant need for highlighters): He read every bill that came through his committees or was presented on the House or Senate floor.

“I’d stay up until 2 or 3 a.m., and be at the Capitol by 6 when it’s nice and quiet,” Wallingford said. “I suppose no one should be expected to put that much time in, but if you’re really trying to do your job right, that’s what I think you should do.”

In the legislature, Wallingford is particularly proud of his work on “raise the age” legislation, upping the age of an adult in the criminal justice system to 18 years old for most crimes.

“It saves our youth. It saves taxpayer dollars because it’s extremely expensive to put someone in prison, and these people would come out of the youth program and be productive citizens, pay taxes, live a normal life,” he said. “And it makes Missouri safer because you don’t have this continued recidivism.”

And in December 2021, Gov. Mike Parson named Wallingford his newest director of the Department of Revenue.

“We look forward to him implementing his vision at DOR to provide the best possible service for the people of Missouri,” Parson said. “There is not a more dedicated public servant that I’ve ever met than Wayne Wallingford, and I look forward to him being part of the team.”

Wallingford has survived a lot in his 75 years besides cancer and combat in Vietnam. He underwent a successful kidney transplant in 2020 and battled COVID-19, the delta variant, last summer.

“What’s next? I just leave it up to the Lord. I try to get ahead of Him, and I find out He’s got a different plan for me,” Wallingford said. “The plan that I had thought would be really great wasn’t as great as the one He has for me.”

Kaitlyn Schallhorn was the editor in chief of The Missouri Times from 2020-2022. She joined the newspaper in early 2019 after working as a reporter for Fox News in New York City.

Throughout her career, Kaitlyn has covered political campaigns across the U.S., including the 2016 presidential election, and humanitarian aid efforts in Africa and the Middle East.

She is a native of Missouri who studied journalism at Winthrop University in South Carolina. She is also an alumna of the National Journalism Center in Washington, D.C.

Contact Kaitlyn at kaitlyn@themissouritimes.com.